On June 24, 2023, Yevgeny Prigozhin – the former convict-turned-entrepreneur-turned-warlord, shook the pillars of the Kremlin. The eyes of the world were riveted on the screens while Wagner mercenaries drove to Moscow. The leader had had enough of Russia’s military leadership that was, in his opinion, responsible for the state of things in Ukraine. Could it be the end of the régime? Few could predict what would happen. At the end of the day, Vladimir Putin prevailed, but the mutiny revealed the character of a man who thought bigger of himself than he could deliver.

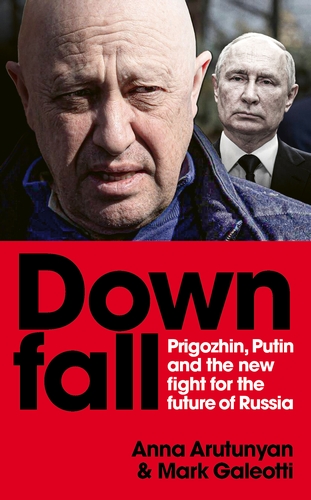

In the recent book Downfall: Prigozhin, Putin and the new fight for the future of Russia (Ebury Press) they co-wrote, journalist Anna Arutunyan and renowned Russia observer Mark Galeotti explain why and how Prigozhin – the servant who forgot his place – embarked on his death knell on what could be described as his highway to hell.

Since Prigozhin intertwined his destiny with Vladimir Putin’s reign, his biography can’t be dissociated from the nature and the functioning of the régime he eagerly served for his good fortune. Comparing the Kremlin to a medieval court where adhocracy prevails, the authors explain that one’s influence and fate are related to its importance to the Tsar.

Encountering Vladimir Putin after he opened “St Petersburg’s first truly top-drawer restaurant”, Prigozhin quickly rose into the presidential sphere. But he never was part of the President’s closest friends – like former Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu with whom he vacationed in the past.

But one can easily understand why Wagner’s founder considered himself an unavoidable asset. After all, “Wagner forces quickly became a key element of the Russian war effort, especially once Putin had abandoned his early push to take Kyiv and instead began to focus on southern and Eastern Ukraine.” A few years prior, Prigozhin’s pugilists had helped “turn the tide of the war” in Syria. The warlord made the Russian President “seem more powerful than he actually was”.

Prigozhin’s main quality, nevertheless, resided elsewhere.

On many occasions, Downfall refers to the fact that Wagner’s actions had to be easily disavowed, deniable, discarded, abandoned and disdained. Prigozhin and his army’s usefulness was tributary to the need to keep them “below stairs” and the capacity to throw them “under the bus.” Changing those parameters would come at a heavy price. A price Prigozhin was only too eager to pay because he found “himself able to enjoy his greatest and most dangerous vice: revenge.”

Revenge, it turns out, proved to be the worst of advisors on Prigozhin’s path – notably because of the nemesis he took on the mat. Prigozhin never shied away from his antagonistic feelings towards Minister of Defence Sergei Shoigu – whom he blamed for Russian setbacks in Ukraine. The travails on the other bank of the Dnipro allowed him to seek the upper hand.

That’s where Vladimir Putin’s governing style came into play. And that’s one of the main contributions of the book. The President, the writers analyze, doesn’t like internal strife and has no appetite for tough decisions. Pushing the President to choose between Wagner’s founder and his vacation buddy was a no-brainer. Shoigu, they write, is a “subtle and dangerous political operator,” and he “ultimately would outmaneuver and outgun ‘Putin’s chef.’” There was no way the longtime friend could lose over the footman lest the President create a mortal precedent.

Prigozhin “overplayed his hand”, and he lost. As a well-read man, he should have known that the servant serves at the king’s pleasure. Playing the king is a risky game. In the “medieval court” that governs Russia, there was, and there is no place for someone who wants to force the king’s hand, sowing disloyalty in the process. Once he rolled on that route, Prigozhin had no choice but to succeed. Stopping midway – while using material provided by the reviled Ministry of Defence lambasted by Prigozhin for its supposed lack of support – could only lead to his pyrotechnical disappearance two months later.

Vladimir Putin, it turns out, knows the kitchens of power better than his former servant. After all, his grandfather, Spiridon, cooked for Lenin, Stalin and their successors for many years. Whether we like him or not, his grandson is a master practitioner of power, and he learned the power recipes well.

Downfall is an excellent biography of a tragic character who contributed to Russia’s fortune in the world in the last few years. It is also an insightful study of the system inside which he evolved. Russia is not about to stop playing a determining role in world affairs, and those who are keen to understand the sinews of the Kremlin can be grateful to Anna Arutunyan and Mark Galeotti for opening an insightful window into the medieval court of the modern-day Tsar – an essential read.

_____

Anna Arutunyan and Mark Galeotti, Downfall: Prigozhin, Putin and the new fight for the future of Russia, London,Ebury Press, 2024, 272 pages.