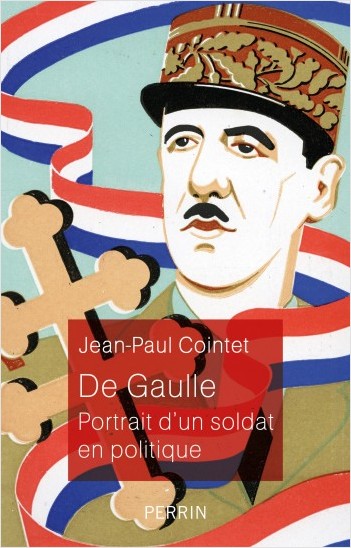

Dans son Dictionnaire amoureux du Général (que j’ai l’intention de recenser ici prochainement), le regretté Denis Tillinac citait De Gaulle qui affirmait : « L’homme d’action ne se conçoit guère sans une forte dose d’égoïsme, d’orgueil, de dureté, de ruse. » Cette citation m’a beaucoup tracassé, parce qu’on a souvent tendance à idéaliser les grands personnages. On les imagine au-dessus des défauts affligeant le commun des mortels. Après tout, le souvenir de leurs accomplissements ne permet-il pas à leur mémoire de prendre place dans l’Olympe des consciences?

J’affirme que cette citation m’a tracassé, parce que la lecture du dernier livre de Pierre Servent, De Gaulle et Pétain (Éditions Perrin) a répondu au questionnement qui m’habitait à propos de l’homme du 18 juin.

Figure d’inspiration de nos jours, De Gaulle a néanmoins cumulé une feuille de route parsemée d’animosité. « Détesté par une bonne partie de l’élite de l’armée », « il n’a guère d’amis dans l’armée ». Il peut cependant, au début de son parcours, compter sur le soutien indéfectible d’un père spirituel hors norme – le Maréchal Pétain – qui lui apprend tous les trucs du métier, dont celui d’être un bon comédien. Une excellente école pour le protégé.

L’auteur nous rappelle qu’au sortir de l’École de guerre en 1924, « Son attitude arrogante, ses contre-performances dans l’exécution de certains exercices qu’il juge au-dessous de son talent naturel, sa difficulté à accepter la critique font que la majorité du corps enseignant souhaite le classer en queue de peloton de la promotion de l’École de guerre, dans le troisième tiers, avec la mention « assez bien ». C’est une catastrophe qui ne se remonte jamais dans une carrière militaire déjà mal engagée. »

J’étais pourtant sous l’impression que De Gaulle était un premier de classe…

Trois ans plus tard, le Maréchal l’impose comme conférencier extraordinaire. De quoi faire rager les détracteurs – et on devine qu’ils sont nombreux – du Connétable. La mauvaise réputation de De Gaulle était notamment assortie du fait qu’il était connu pour être un chef très dur et distant envers ses subalternes.

À priori, on serait porté à croire qu’un tel patronage s’accompagnerait d’une loyauté sans faille. Pas pour De Gaulle, dont la boussole personnelle est orientée par son destin et celui de la France. S’il faut trahir une vieille amitié pour y arriver, qu’il en soit ainsi.

En 1938, De Gaulle fait accepter le manuscrit de La France et son armée par un éditeur, Plon, lequel ignore « […] que son nouvel auteur publie un texte qui, d’une certaine façon, appartient à un autre […] ». Le livre résultant d’une commande passée du maréchal sera publié et la rupture entre les deux hommes sera irrémédiablement consommée. Le vin est tiré… Et la table est mise pour la scène légendaire qui se jouera quelques mois plus tard.

De Gaulle n’a pas hésité à grimper sur les épaules de son protecteur pour se hisser au faîte de la gloire, une gloire néanmoins chèrement acquise dans les sacrifices encaissés sur la route de l’exil pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Lorsqu’il aborde le thème de l’orgueil – une caractéristique arborée fièrement par les deux protagonistes de son récit – Pierre Servent se déploie à multiplier les qualificatifs : cosmique, incommensurable, sans bornes, immense, puissant, d’airain, himalayen… Mais aussi bafoué et blessé. Comme pour nous rappeler que le destin des grands personnages est forgé au feu des épreuves et que les orgueils surdimensionnés constituent un rempart protégeant une sensibilité ne voulant pas s’exposer. Des épreuves que tout un chacun peu à peine imaginer. Je repense, en écrivant ces mots, à la séquence du film mettant en vedette Wilson Lambert et Isabelle Carré – que j’ai eu le privilège de visionner avant son retrait des salles de cinéma du Québec à cause de la COVID-19 – au cours de laquelle on voit le personnage principal quitter fin seul la France en juin 1940.

Pour devenir un artisan de l’histoire, De Gaulle avait compris qu’il ne faut pas être aimable et docile, mais qu’il fallait savoir ramer à contre-courant, contrairement à son ancien mentor qui profitait de la vie bonne dans la thermale Vichy.

Le maréchal Pétain fut certes le professeur généreux du Général de Gaulle dans la période formatrice de sa vie. La capacité de l’élève à se démarquer – certains diront à tuer la figure – du maître, lui aura permis de se détacher de tout en juin 1940 pour mieux attacher son wagon à la locomotive de l’histoire.

Sous la plume animée de cet éminent spécialiste en histoire militaire – qui nous a réservé d’autres bons livres comme une excellente biographie du Feld-maréchal Erich von Manstein et L’extension du domaine de la guerre que j’avais beaucoup apprécié – on apprend que le destin a un prix, celui de ne croire qu’en soi. Contre vents et marées. Une leçon puissante, surtout en cette période difficile.

_____________

Pierre Servent, De Gaulle et Pétain, Paris, Éditions Perrin, 2020, 224 pages.

Je remercie Mme Marie Wodrascka, des Éditions Perrin, qui m’a aimablement fourni un exemplaire de cet excellent livre.

Winston Churchill a toujours occupé les premières loges de ma passion de l’histoire. Sa relation avec Charles de Gaulle m’a toujours fasciné, notamment en raison des nombreuses similitudes entre ces deux grands : impulsivité, génie, mélancolie passagère, éloquence, sens de l’histoire, caractère rebelle et j’en passe.

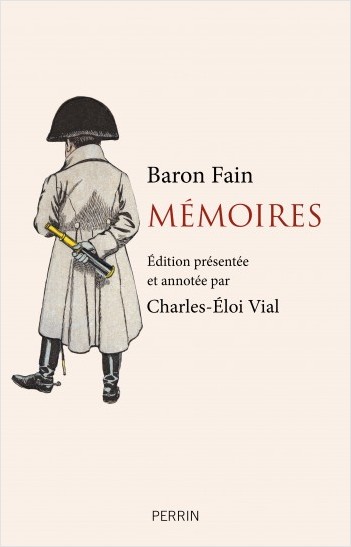

Winston Churchill a toujours occupé les premières loges de ma passion de l’histoire. Sa relation avec Charles de Gaulle m’a toujours fasciné, notamment en raison des nombreuses similitudes entre ces deux grands : impulsivité, génie, mélancolie passagère, éloquence, sens de l’histoire, caractère rebelle et j’en passe. Napoléon fascine notamment par son génie militaire et l’empreinte qu’il a laissé dans l’histoire. Mais ce qui m’a toujours fasciné davantage, c’est l’homme et ses ressorts. Qu’est-ce qui le motivait, comment pensait-il et comment travaillait-il? Je piaffais donc d’impatience de plonger dans la récente édition des

Napoléon fascine notamment par son génie militaire et l’empreinte qu’il a laissé dans l’histoire. Mais ce qui m’a toujours fasciné davantage, c’est l’homme et ses ressorts. Qu’est-ce qui le motivait, comment pensait-il et comment travaillait-il? Je piaffais donc d’impatience de plonger dans la récente édition des

In Sailing True North, one of my favorite chapter (with the one devoted to Nelson) is the one about Zheng He. What do you think of the current tense situation with China and how do you think we should deal with that?

In Sailing True North, one of my favorite chapter (with the one devoted to Nelson) is the one about Zheng He. What do you think of the current tense situation with China and how do you think we should deal with that?

As I read these words, the New York Times revealed last Sunday that “

As I read these words, the New York Times revealed last Sunday that “